My Building Has Every Convenience

David Byrne attempts to turn a derelict ferry terminal into one immense musical instrument.

By Justin Davidson, New York Magazine, 1 June 2008 [Link]

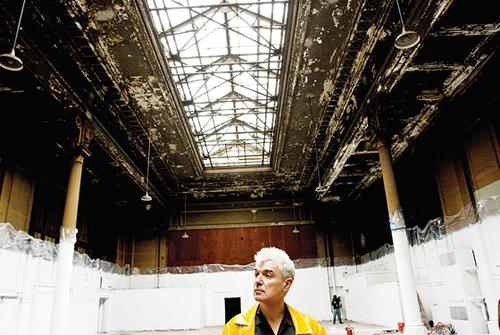

Aharon Rothschild/Metro New York/Courtesy of Creative Time

A battered pump organ sits on the concrete floor of the peeling and long-abandoned great hall of the Battery Maritime Building. Tubes and wires trail off into the rafters, as if either the instrument or the architecture were in critical condition and one were keeping the other on life support. Actually, the two have been hooked up to make music, or something like it. I approach the keyboard and tap a low A-flat, and the building gives a staccato rumble, like a walrus’s burp. I finger a few high notes and release a sequence of tuneful clanks. The middle part of the keyboard yields a wheezing, ghostly choir. If walls could sing, this is how they would sound. Entranced, I would like to stay all night and learn to play the thing properly.

David Byrne, who interprets the term artist with marvelous expansiveness, doesn’t actually play the building in Playing the Building; it’s visitors who make the sounds. He made the architecture orchestral—feeding air into flutelike heating pipes, triggering hammers on cast-iron columns, and vibrating motors against ceiling beams as if drawing a bow across the strings of a giant fiddle. Having put in place the machinery, he has already moved on, letting the public serenade itself. In an interview published on his Website, he remarks that he hopes to offer “an experience in which one begins to reexamine one’s surroundings and to realize that culture … doesn’t always have to be produced by professionals and packaged in a consumable form.”

Yet this installation also shows the severe limitations of this democratic, do-it-yourself approach to art-making. For one thing, I doubt it’s really possible to master the resonating building. Byrne’s creation is the opposite of the music-making software on your laptop that can make an 8-year-old D.J.’s tinkerings seem passably professional. The architectural organ would defeat a virtuoso. It’s a primitive instrument, which is the core of its charm: No amplification, no computers—just a science-project contraption that coaxes the building to surrender its own latent vibrations.

Byrne acknowledges the precedents in John Cage, Brian Eno, and other ambient tinkerers, and he has also talked about his attraction to the steampunk aesthetic, a fusion of homemade technology and antique décor. But this is not just a piece about style, and it doesn’t strike an ironic pose. It’s sincere in its simplicity, though a little coy about who, exactly, is producing what kind of art. Nominally, the visiting “performer” is at the controls, and maybe one person’s cosmic shuddering will come out a little more refined than another’s. But the experience mostly consists of inhabiting the building’s sound world, and whether you’re listening to others manipulate the keys or doing it yourself doesn’t really matter. Later, when I emerge from that weirdly sacramental space, the rush-hour clangor of lower Manhattan acquires a fresh kind of clarity. The buzz of the Battery underpass, the nasal honk of the Staten Island Ferry, the pneumatic hiss of a kneeling bus, all seem suddenly deliberate, as if someone had wired the entire city and a stream of visitors were amusing themselves on a keyboard trying to get the thing to speak.

Playing the Building was commissioned by Creative Time, an organization that sprinkles ephemeral artworks around the city, prodding people to notice things they might otherwise stride by in a daze. This project brings out the lyrical obsolescence that is one of the Battery Maritime Building’s most enduring characteristics. Built in 1909, it served as a terminal for the Brooklyn ferry lines, which were already losing the competition with the Brooklyn Bridge. Ferry service ended in 1938, and the building has been searching for a purpose ever since. With its green steel arcade and gracious trim, it looks glamorously lonely on Manhattan’s southern edge, as if it were perpetually on the verge of slipping into the water and going for a swim. One corner hosts ferry service to Governors Island. A developer is buffing plans to plunk a four-story glass hotel and restaurant down on top. The great hall still lies fallow. Its naked girders, the ones Byrne’s organ sets to vibrating, once supported a stained-glass ceiling. That’s gone, but the peaked skylight lets sunshine cascade into the hall and lends it the atmosphere of an abandoned basilica, haloing the organ like an altar. That old keyboard sitting alone in the quiet, vacant space has the feel of a ritual object or a Victorian invention, or both, making Byrne’s sound installation a marriage of the industrial and the sublime.