David Byrne: Sonic Architect

The former Talking Head's latest bizarre and brilliant scheme

By Rob Harvilla, The Village Voice, 3 June 2008

[Link to article] [PDF of article]

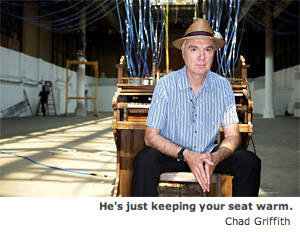

"So, what do you want to know?" asks David Byrne, beaming beneath a straw fedora, as erudite and affable as ever, even with a couple busted ribs. "What's not apparent?" He's gesturing to an ornate antique organ, the only adornment to this cavernous 9,000-square-foot hall in the Battery Maritime Building in Lower Manhattan. A bewildering farm of tubes and wires runs out from the back and snakes along to the walls, the towering columns, and the pipes looming overhead, as if the instrument itself were on life support. Not much, at first blush, is apparent.

"So, what do you want to know?" asks David Byrne, beaming beneath a straw fedora, as erudite and affable as ever, even with a couple busted ribs. "What's not apparent?" He's gesturing to an ornate antique organ, the only adornment to this cavernous 9,000-square-foot hall in the Battery Maritime Building in Lower Manhattan. A bewildering farm of tubes and wires runs out from the back and snakes along to the walls, the towering columns, and the pipes looming overhead, as if the instrument itself were on life support. Not much, at first blush, is apparent.

David would like it if you came and had a go at the organ. Or, more accurately, the venue itself. Playing the Building, his partnership with arts gurus Creative Time, is basically an interactive experimental-music station, a chance for you (and/or your kids) to pretend you're a member of Einstüerzende Neubauten for a couple minutes. Each key on the organ connects to a tube, which connects to some facet of the building, which dutiful whirls or clanks or whistles or saws at your command. The tones are generally arranged low to high on the keyboard, though you can't exactly play "Stormy Weather" on it; it'd be more satisfying, perhaps, to rattle off a few full-keyboard slides, Bugs Bunny/Jerry Lee Lewis–style, though so far, everyone seems too polite (or too fearful of busting the thing) to do this. Probably just as well. Your choice, though. Spray-painted in yellow onto the cement floor at the foot of the organ is a simple request: "Please play."

Holding court and testing errant keys a few days before the exhibit's grand opening this past Saturday—it's now open to the public Friday through Sunday, from noon to 6 p.m., until mid-August—David stresses that he's not a musician here, but a facilitator. It's his gift to the masses: "It's nice that they can come in and play the thing," he says. "It's not a piece of music that you download or you buy, something like that. It's something that you actually have to sit and do." Furthermore: "You can see how it works. It's not like a piece of software where the actual workings of it, unless you're a real techie, are completely hidden to you. It's pretty easy to see which ones are blowing air."

The ex–Talking Heads frontman—who, after a couple decades of fantastically strange projects (deadpan PowerPoint presentations, a McSweeney's-approved faux Bible treatise entitled The New Sins, that musical about Imelda Marcos, etc.), finally feels like he's shed the Rock-Star-Makes-Art tag and can stand on his own as a conceptual artiste—first mounted Playing the Building at an old factory in Sweden a couple years back. He remembers fondly the empowerment it engendered among folks there: "They didn't feel inhibited about playing the thing. They didn't feel like they were amateurs and only professionals can play it. They didn't feel like it requires a composer or a musician to play, because obviously it's not like a regular instrument. So that, I think, helped loosen people up—and kids and adults and whatever, they all felt they could have a few minutes fooling around on it."

The ex–Talking Heads frontman—who, after a couple decades of fantastically strange projects (deadpan PowerPoint presentations, a McSweeney's-approved faux Bible treatise entitled The New Sins, that musical about Imelda Marcos, etc.), finally feels like he's shed the Rock-Star-Makes-Art tag and can stand on his own as a conceptual artiste—first mounted Playing the Building at an old factory in Sweden a couple years back. He remembers fondly the empowerment it engendered among folks there: "They didn't feel inhibited about playing the thing. They didn't feel like they were amateurs and only professionals can play it. They didn't feel like it requires a composer or a musician to play, because obviously it's not like a regular instrument. So that, I think, helped loosen people up—and kids and adults and whatever, they all felt they could have a few minutes fooling around on it."

But the piece has added resonance in New York City, first of all from the real-estate angle, stemming the tide (albeit briefly) of all our weird, old, eccentric buildings slowly succumbing to Starbucks franchises and McCondos. This will be the public's first trip to the Battery Maritime Building's second floor in decades, and care was taken to preserve the atmosphere: Short of the obvious, rudimentary cleanliness/safety issues, Byrne chose to leave the raw, industrial, bluntly intimidating space largely alone. (Which may explain why you have to sign a waiver to get up there.) "The EDC [Economic Development Corporation] . . . their motivation is to get some developer in, which I think is eventually gonna happen here," Byrne says. "Somebody's gonna do something in here that's more commercial than this. But in the meantime, they like having this kinda stuff in, because it draws attention to the space, gets it in the news a little bit."

What's also NYC-specific is the "music" itself, specifically its strong resemblance to the ambient, everyday street noise we either take for granted or push out entirely via noise-cancelling iPod headphones: The organ can sound remarkably like traffic, like construction, like an old building wheezing as you walk by. (The sort of thing, coincidentally, you're probably more attuned to if you're on a bicycle. Byrne is an avid cyclist, which is how, unfortunately, he got those busted ribs—he recently wiped out on West 14th Street, upon which two cops appeared and immediately wanted to know if a) he'd been drinking and b) he was David Byrne. Yes to both questions.) Playing the Building gives you the chance to rehear the city's true heartbeat and control it.

Stopping by Saturday afternoon for the grand opening, there's a line of 20 to 25 people patiently waiting to do just that—intriguingly, many choose to attack the organ as part of a duet, though you can't exactly play "Heart and Soul" on it either. Very small children seem more impressed with the noise they can make slapping their hands on the keys than the bells and/or whistles themselves; slightly older kids tend to prefer staring at the guts of the thing, the intricate wiring and pressure gauges visible within. Some people stroll around tracing the vines to the noisemakers they lead to; others just lie on the concrete floor, close their eyes, and soak it all in.

Perhaps the simplest statement being made here is that You, Too, Can Be a Musician, a salient point when the monolithic music industry that helped boost Talking Heads to prominence is in free-fall, but a young, unknown musician has more weapons and potential outlets than ever. This is not David's only dalliance with this idea: On his excellent blog/journal at DavidByrne.com, he recently discussed his attempt to design a carpet of 100 guitar pedals that everyone would have to walk on to enter a benefit for the Kitchen. While this was an even more physical, visceral method of impromptu music-making, he hadn't anticipated a few problems—women in high heels, for example: "Well, we had problems with the building manager on that piece, so I had to pull it out," he tells me. "But I'll try it again somewhere else." It'd be nice if he had an infinite amount of time, and a never-ending glut of available and charismatic places to do that. But in reality, he might want to hurry.