The Whole World, In His Hands: David Byrne Brings His Art to the High Line

By Andrew Russeth, The New York Observer, 13 September 2011 [Link]

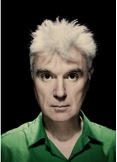

Photo by Clayton Cubitt

After the Pace Gallery’s Marc Glimcher completed his recent purchase of prime real estate beneath the High Line between West 24th and 25th streets—it abuts one of Pace’s two branches on 25th Street—he faced a dilemma: what to do with the empty space before construction began on the new gallery he plans to open there in fall 2012? “I thought, O.K., we need the old demolition party, or something like that,” Mr. Glimcher, Pace’s president, told The Observer.

But then Mr. Glimcher’s wife, Andrea, the gallery’s communications head, who he said had been the driving force behind the acquisition of the space (“As usual, she got what she wanted”), had another idea. “She thought that this would be the perfect place to do a project with David,” he explained, referring to David Byrne, the former lead singer of the new wave band Talking Heads who has since ventured into the art world.

“I first encountered David’s work in the 1970s,” Mr. Glimcher said. “The fact that I waited at the stage door, trying to get an autograph from Dave back then is not important to the story.” He laughed. “Actually, I just found my pin from the concert they did in Central Park, which was nice. But I digress.”

When The Observer visited Mr. Byrne’s Soho studio recently, a drawing of the artist’s proposal for under the High Line hung on one wall: a giant light-blue globe squeezed underneath, pushing up against the bottom of the park and the two side walls, as if it had just popped in from another dimension, or an elementary school classroom.

“You couldn’t hang art on the walls because it’s too messy,” Mr. Byrne, 59, told us. He sat at a desk in the loft, and was wearing a green shirt and white pants. He looked as though he’d forgotten to age, appearing nearly the same as he did in photographs 30 years ago—slim and tall, and a little imposing, though his hair is bright white these days instead of black, which gives him an air of erudition. He had recently returned from a trip through South America, during which he discussed bicycle use, one of his favorite topics.

“You could put a big solid object in there,” he said, speaking of the High Line space, “but it wouldn’t look any more impressive than anything else stashed in there.”

The lot is often filled with parked, rundown cars from a nearby automobile repair shop and all manner of debris and garbage. “You have a lot of visual competition,” said Mr. Byrne, holding up a miniature model of the lot and the High Line that Pace’s fabrication team had made for him. “It had to be something that really takes up the space. I thought, ‘Ah, a balloon—an inflatable balloon.’” There was a tiny replica of the globe sandwiched under the miniature High Line.

He made all of this sound matter of fact, almost straightforward.

Not surprisingly for a musician, the giant globe has an audio component, a low rumble that will come from inside its belly, which he created by singing and then processing his voice. “It kind of goes wooo woo woo wooo,” Mr. Byrne said. “Actually that’s pretty much exactly the sound it makes. If we can get it loud enough, but not be totally obnoxious, it will draw you—as sound can do—to look in there, either down from the High Line, or from the street.”

He continued, almost whispering. “You’ll say, ‘What’s in there?’ That’s the idea anyway.”

“It’s the last thing I imagined—something crushed in there,” Mr. Glimcher told us. “But besides all the allusions that come along with it, it’s just a fantastic definition of that space.”

For his part, Mr. Byrne described his globe largely in formal terms. He purchased a variety of grade school globes and globe beach balls, and experimented with color choices. The work features political boundaries and major cities but few topographical markers. “I didn’t want one that shows all the geographical features,” he said. “That would hammer the ecological idea or climate change idea. It would go right to that. Then it really looks like our planet being squished by a highway.”

As is immediately apparent to anyone who visits his studio, Mr. Byrne does more, in the visual art department, than merely make giant globes. In one corner of the room were chairs that he had made—a roomy one constructed out of atom models, and a narrower, straight-backed one lined with macaroni. The walls were covered with art, including, in one room, a long drawing by the reclusive outsider artist Henry Darger that Mr. Byrne purchased about three decades ago from the Soho gallerist Phyllis Kind, just after the art world’s posthumous discovery of Mr. Darger’s work, before it really took off.

Mr. Byrne has been painting. While The Observer spoke with him, he worked on a composition on a large sheet of paper. When he showed it to us, we saw a large blowup of an Apple iPad app called GottaGo. Inside the tiny square reserved for the icon there was an open mouth enclosed within a giant red circle and slash.

“It automatically drops your phone call,” Mr. Byrne said, as he traced the red lips of the mouth and began filling it in. “It makes it seem like the phone has had a glitch or that the service provider has suddenly just dropped your call, so that way you can get out of any call.” He laughed. “No call lasts longer than two minutes!”

He’s created a whole series of these paintings of imaginary apps that offer users farcical, absurd and occasionally sinister programs. The text of an app called Childster explains that it “turns your phone into a babysitter!” Bigamist is “an online service that manages your cheating!”

The titles are not the sarcasm of a Luddite—Mr. Byrne has both an iPhone and iPad, and he uses apps, like OpenTable, for booking restaurants, and Kindle, for reading electronic books. It’s just that he thought there were a lot of apps—maybe more than anyone could ever really need. “There was a new article every week saying, ‘Look, now there’s an app for this and this. This will coordinate your driving habits with your real-estate needs,’” he said. “I just thought, you know, this is out of control!”

The app paintings will go on view at Pace’s 510 West 25th Street branch this Thursday as part of a group show called “Social Media,” the same day that the gigantic globe, Tight Spot, will be presented to the public next door. “Social Media” was conceived by Peter MacGill, the president of the Pace Gallery’s photography arm, Pace/MacGill. “I watch MSNBC every morning,” Mr. MacGill told The Observer. “Earlier this year I saw how fast Facebook and Twitter were changing things, how incredibly fast dictators were falling. I said, ‘This is an exhibition.’”

Besides Mr. Byrne’s work, “Social Media” features a number of other pieces related to the Internet and social networking, including artist Jonathan Harris’s I Love Your Work (2011), a series of videos documenting the lives of models of internet porn models and an excerpt from Learning to Love You More (2002-09), the project by artists Miranda July and Harrell Fletcher that asked people to craft responses to various prompts on a website, which were then posted online.

Mr. MacGill—who first began working with Mr. Byrne after meeting him through Robert Rauschenberg—saw the fantastical apps on a studio visit and was charmed. “It was pure David Byrne,” he said, “because it was utilizing something available to all of us, and making it into something aesthetic, creative and critical.” (One of Mr. Byrne’s earlier shows at Pace/MacGill featured a PowerPoint presentation about PowerPoint presentations, which was later sold as a book and a DVD.)

And almost the entire look of his apps is predetermined. “You can go online and get a template for all the Apple stuff,” Mr. Byrne said, “the type faces, the drop shadows, the gray fade in the background.” He writes text, prints it out, then paints a little icon in the prescribed position.

Painting, though, is hardly Mr. Byrne’s usual practice—he has typically been far better known for his large-scale installations and public art projects. In 2008, he outfitted the Battery Maritime Building in downtown Manhattan with a keyboard attached to various rods, solenoids and motors. As people tapped the keys, girders, pipes and radiators created strange and beautiful music. It also appeared in Stockholm, Sweden, in 2005, and traveled to London after its stay in New York.

That same year, he designed whimsical bike racks—shaped as a silver dollar sign for Wall Street, a scantily clad woman for Times Square—for the Department of Transportation. Pace offered to cover the fabrication costs if it could sell the racks or create an edition of them. “Nobody bought them,” Mr. Byrne said. Instead, the city voted to leave them in place beyond their one-year run.

“I’m kind of their public art guy in a way,” Mr. Byrne said of his relationship with Pace. That’s a position that would irk some artists, but he was delighted. “I actually love that,” he said. “I don’t know how it works for the gallery because they don’t have anything to sell. After the other projects I thought, ‘Eventually you’re going to need some income here, guys.’”

Mr. Byrne thinks his globe could be shown elsewhere, if the space is right. “I just sent a picture of it to a guy who has a gallery in Guadalajara,” he said. “They have an elevated highway that runs right through the center of town that’s very contentious because it’s new, it cost a lot of money, and it’s a question of, ‘Why did you put this Robert Moses work right through the middle of our town?’

“But it’s beautiful,” he said, “and if the height is correct, it would fit under there.”

We put the question of the globe’s salability to Mr. Glimcher. “It’s a philosophical question, don’t you think?” he said, with equanimity. “You never know. You have to go into projects like this like it’s a total leap of faith. If they work—and this is going to work—they become like his organs, they become itinerant minstrels, and they go and play their song somewhere else and somewhere else.”