|

David Byrne on New Urbanism, Burning Down of Houses at CNU 18

By Greg Lindsay, Fast Company, 20 May 2010 [Link]

If you were in the market for an introduction to the New Urbanism -- what is it for? what is it against? what is it about, really? -- your choices on the opening day of the Congress of the New Urbanism (CNU 18) were either a seven-hour seminar with some of the rock stars of the movement (Andres Duany and Georgia Tech professor Ellen Dunham-Jones) or a deceptively modest 20-minute slide show with an actual rock star, David Byrne.

The polymathic Talking Head has been a critic of sprawl and other soul-dead environments for quite a long time. This is a man who once published a book of absurdist PowerPoint art, not to mention co-wrote the lyrics to "Burning Down The House":

Watch out you might get what you're after

Cool baby strange but not a stranger

I'm an ordinary guy

Burning down the house

Hold tight wait 'til the party's over

Hold tight we're in for nasty weather

There has got to be a way

Burning down the house

Prior to the conference, he confessed to Creative Loafing that he was no fan of Atlanta's landscape, either. "Yeah, the sprawl is fascinating -- like ogling something bizarre and grotesque…. There are reasons why Detroit is almost gone and why Phoenix is sinking fast and I’d be very surprised if a lot of the homes built in recent years on the fringes of the Atlanta metroplex actually have people living in them. I think the big bad wolf hasn’t come to Atlanta yet, but I suspect he will pay a visit pretty soon."

He's even published his own book on urbanism, last year's Bicycle Diaries, which dovetailed nicely with the New Urbanist's love affair with two wheels. In fact, if you were to choose an artifact which personifies their ideals, it would probably be the bicycle -- an elegant, people-powered, sustainable machine for living that's faster than walking (and thus able to increase the scale of daily activities) but not too fast.

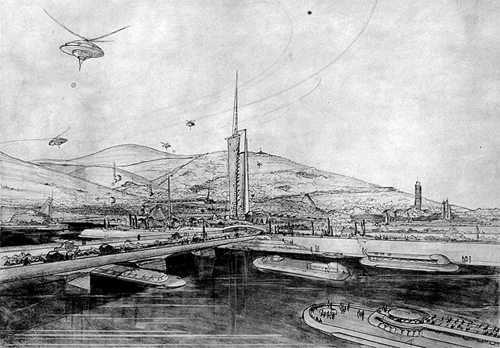

What is New Urbanism against? Byrne listed examples. There was the "Broadacre City" proposed by Frank Lloyd Wright (who hated the squalor of cities in industrial America), which prefigured exurban sprawl. "There's lots of farmland," narrated Byrne, "and there's a building over there, and the people come into contact very much, and when they do, it's by these flying saucers… (an "aerator," actually -- a helicopter that could land without a landing strip). "He was a great architect, but thank god he didn't make cities."

Then there's Buckminster Fuller, "who wanted people to live in these cooling towers" -- cylindroid towers that would have replaced most of Harlem. And finally, there's Le Corbusier ("Corbu!") who proposed the geometric towers of the Radiant City. "This one, sad to say, did come true in many of our cities," Byrne said. "'We must kill the street,' he said, and it did come true.'"

What followed was a series of slides depicting the consequences: parking lots in downtown Nashville, Boston, and Houston. "Everything that surrounds that acreage is a deadzone," he said. "They're storage facilities for metal canisters, and they have no place in the center of our cities."

"I think Le Corbusier, as beautiful as some of his structures are, has given cities an attitude that has turned them against their own citizens. But it doesn't have to be that way."

In his typically quirky way, Byrne proposed his own solution -- bicycles, and the urban forms they embody: narrow, walkable streets (preferably without cars) in Tokyo, Mexico City, New York's Time Square, and the medieval towns of Italy. (New Urbanists seem to have a fetish for Italy.) He left out the Dutch city of Groningen, where 58% of all journeys are made on bicycles in a city of 180,000 people (and 300,000 bikes).

More slides followed of bike storage systems in China, Tokyo, and Chicago, followed by a few brief glimpses of bike-sharing programs in Paris and Montreal, the economic benefits of bicycle use for cities (as Austin discovered this spring).

A digression on electric bicycles led to a digression on electric concept cars "similar to the bike in that there's no motor in the car; like the bike, it's in the wheel. Obviously there's a big battery in there somewhere. The idea is that these all link together. If you bike to a destination, could share all this stuff."

He noted many cities were beginning to pave over freeway and placing parks on top, a la Boston's Big Dig. His on-screen list included freeways in Cincinnati, Dallas, Minneapolis, St. Louis, San Diego, Santa Monica, and Seattle. "In New York, if only we could bury the West Side Highway and FDR Drive," he suggested to cheers.

But can bicycles and cars co-exist in America? He was optimistic--they already are. Cycling injuries in New York have fallen from more than 5,000 in 1998 to less than 3,000 by 2006 and has stabilized around that level. (Better signage helps.)

As for the sweat issue, he flashed a slide of a dapper gentleman riding a bike. "This guy's the head of Louis Vuitton in New York, and he wears the whole suit."

"And that's the end of my talk."

|