E.E.E.I. |

"Using PowerPoint Analyzed by Artist"

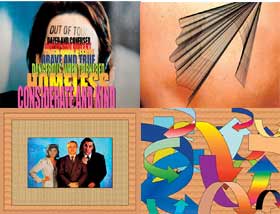

David Byrne, formerly the front man of the rock group Talking Heads and currently a solo musical and visual artist, delivered what may have seemed a somewhat uncharacteristic lecture on March 10 to a full house at UC Irvine’s Humanities Instructional Building. Entitled “I ♥ PowerPoint,” Byrne’s lecture was a surprisingly straight-faced espousal of the merits of the popular Microsoft computer program, with which users can create professional-looking slide-show presentations. Byrne’s lecture, which was the penultimate stop on a tour that included stops at UC Berkeley, UC Santa Barbara and UC Los Angeles, drew from his 2003 book and DVD set entitled “Envisioning Emotional Epistemological Information,” in which Byrne showcased artwork that he had created utilizing PowerPoint. “I do these things that are kind of like little abstract films, or whatever, and I use PowerPoint,” Byrne said. Some pieces from Byrne’s DVD were shown at the beginning of the lecture, such as “Physiognomies,” in which images from old publications on phrenology and silhouettes of disembodied heads crept onto the screen, only to dissolve into photographs of eyes, mouths and other body parts. Byrne’s lecture, although inspired by his work in the medium of PowerPoint, actually focused very little on his creative work and more on the benefits and detriments of the computer program. “I’m actually not going to talk about my work that much,” Byrne said as he took the stage. “Um ... sorry.” Byrne then proceeded to launch into a tongue-in-cheek overview of PowerPoint, accompanied by slides bearing titles such as, “Bullet Points: What do they do? Do I need them? Will they make my presentation more effective?” “[Bullet points] are like exclamation marks before the phrases,” Byrne said. “They tell you, ‘This is really important.’ ... When people make PowerPoint presentations, they tend to condense the points they want to get across into short, pithy phrases.” Byrne’s introduction also made extensive use of slides that he had found on the Internet in order to illustrate how pervasive the software is. “I looked around to see how PowerPoint was being used,” Byrne said. “It’s used in teaching. It’s used in marriage counseling.” Another PowerPoint artist, Daniel Radosh, has even translated great works of literature into PowerPoint presentations. Byrne drew big laughs when he displayed one of Radosh’s slides based on William Shakespeare’s “Hamlet.” The slide compared the pros and cons of “Option One: To Be” and “Option Two: Not to Be.” Byrne also presented a brief history of PowerPoint, from Whitfield Diffie’s development of a process to print graphics and text onto a sheet of acetate for use with an overhead projector, to Bob Gaskin’s development of a prototypical computer program, to Microsoft’s eventual acquisition of Gaskin’s company. In spite of an introduction that seemed to make light of PowerPoint’s contributions to American culture, Byrne’s presentation turned serious when he began a sincere discussion of PowerPoint’s effects on society. “Although it’s kind of easy to laugh at some of the aspects of PowerPoint ... as a program, as something that people use to convey information, it’s maybe a symptom of something larger,” Byrne said. “It’s a sort of Cartesian thinking. [...] If we can just name everything and identify everything and make a humongous flowchart that encompasses a good part of the universe, including ourselves, then we’ve nailed it.” Byrne presented some of the criticism leveled against PowerPoint, much of which comes from Edward Tufte, a professor of statistics and graphic design at Yale University. “[One of Tufte’s criticisms is that PowerPoint] makes people feel that they are communicating something and it makes audiences feel that something is being conveyed, though it isn’t necessarily so,” Byrne said. “In most cases, nothing’s coming across whatsoever.” Byrne said that such a view was incomplete because the actual slide show is only part of the overall experience. “What’s going on in the presentation isn’t in the slide,” Byrne said. “It’s what happens between me and the audience—the way my voice sounds, the gestures I use. ... The communication happens in the whole dynamic that’s going on there.” Byrne likened PowerPoint in some respects to Eastern theatrical productions and the works of playwrights like Bertolt Brecht and Antonin Artaud. “PowerPoint is a form of theater,” Byrne said. “It has [a lot] in common with Asian theater and developments in modern theater. The stage mechanisms are revealed. They are not hidden. ... PowerPoint is like that. It comes with the laptop and the podium and the stage. It’s a type of performance.” Byrne’s presentation seemed befuddling to some in attendance. Some in the audience left in the middle of the lecture. One questioner at the end of the presentation expressed surprise that Byrne did not incorporate any music into his performance. For others, however, Byrne’s presentation was very enjoyable. “It was actually very provocative and opened up new possibilities with PowerPoint,” said Robert Colson, a graduate student in English. “He’s a conceptual artist. It moved beyond satire.”

|