Indie Rock’s Patron Saint Inspires a New Flock

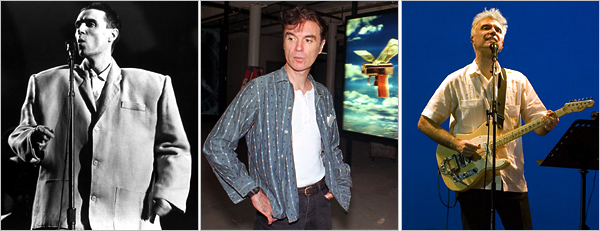

Wearing a striped sports jacket and very sharp blue suede shoes, David Byrne stepped into an elevator at 32 East 57th Street in Manhattan last October. He was on his way to the Pace/MacGill Gallery for the opening of his art show “Furnishing the Self — Upholstering the Soul.” Mr. Byrne was alone and running a bit late; the reception had begun a half-hour ago. “Anybody up there?” he asked cheerily. Of course there was. There was a healthy crowd: a mix of what looked like well-heeled uptowners, scruffy Brooklyn bohemians and clean-scrubbed Asian art students. But those who still saw Mr. Byrne as the singer from Talking Heads, who came to catch a glimpse of a real live rock star, were surely surprised by the modesty of the event. And anyone might have been surprised by the artwork itself: simple, whimsical studies of chairs, either drawn with ink on paper, embroidered on framed furniture upholstery or constructed from odd materials, including a steel file cabinet, old encyclopedias and uncooked macaroni. Yet the show (which has closed, but is documented at davidbyrne.com) was consistent with the idiosyncratic tone of Mr. Byrne’s whole post-Talking Heads career, which has balanced playfulness and erudition with a dollop of disorientation. He has been an author and photographer (the book “Strange Rituals”), a film director (the documentary “Ilé Aiyé” and the feature film “True Stories”), a television host (the sadly defunct PBS performance series “Sessions at West 54th”), a PowerPoint programmer (the DVD/book “E.E.E.I. (Envisioning Emotional Epistemological Information),” which documents his attempt to recast the Microsoft presentation software as an art medium), a record producer, a soundtrack composer. These days this 54-year-old polymath has been particularly busy. He is the curator of the 2007 Perspectives series at Carnegie Hall, which next month will feature a program of experimental folk music (including Vashti Bunyan, Devendra Banhart, Vetiver, Adem, Cibelle and CocoRosie) and a multi-artist concert based on the conceit of a single drone note. It will also include two nights of Mr. Byrne’s work: a performance of music from “The Knee Plays,” his 1985 theatrical collaboration with Robert Wilson, and a preview of “Here Lies Love,” his new multimedia song cycle based on the life and reign of Imelda Marcos, the former first lady of the Philippines. If that seems an unlikely subject, well, consider the fact that Mr. Byrne, like Ms. Marcos, clearly appreciates a good pair of shoes. “Hush Puppies came out with all these wild colors like seven, eight years ago,” he said after his opening, referring to his turquoise footwear. “I thought: ‘Who the hell is going to buy these? They look like they’re for some Vegas singer.’ I figured they wouldn’t be around long, so I got those and a yellow pair and a lime-green pair.” Perhaps more surprising is that while Mr. Byrne has been busy being a curator, sculpturing, drawing, mounting theatrical pieces about deposed foreign leaders and buying shoes, he has also become, without fanfare or Talking Heads reunion tours, perhaps the single greatest influence on the current generation of indie rockers. Four of the most hotly anticipated CDs of 2007 — by the Arcade Fire, LCD Soundsystem, !!! and Clap Your Hands Say Yeah — are coming from bands that, each in its individual way, show a clear stylistic debt to Mr. Byrne and his old group.

Once the archetypal nerve-racked data-age persona (his famously uncomfortable 1983 Letterman interview is on YouTube, if you need a reminder), Mr. Byrne is today much more mellow. He seems comfortable in his skin, chatty and quick to laugh; his conversation ranges energetically from computerized embroidery machines to a recent visit to a neuroscience lab in Canada with his pals from the Arcade Fire. (“We didn’t get a chance to get into the M.R.I. machines,” he said, “but we had a lot of fun.”) He has even become a blogger, and a self-disclosing one at that. “I was a peculiar young man,” he wrote in a reflective entry last April. “Borderline Asperger’s, I would guess.” Lately Mr. Byrne has also been creating book-art projects with the writer and graphic designer Dave Eggers. The most recent is “Arboretum,” a reproduced sketchbook of curious free-associative riffs in the form of evolutionary trees and Venn diagrams that he prefaced with a series of questions: “What are these drawings? Why did I do them? Will they be of interest to anyone else? Of any use? Do they need to be useful?” Here’s another question: Why so many media? “Some are better for saying a particular thing than others,” Mr. Byrne explained. “I think it’s also part of that punk do-it-yourself attitude, of being like: ‘Well, I don’t care that I’m not an expert in this. I know my limitations, but I think I can express what I want to express within those limitations.’ You know — like I may only know three chords, but that’s all I need.” Mr. Byrne knows far more than three chords. And having attended, albeit briefly, the Rhode Island School of Design, he is not a fine-art naïf. But his can-do attitude appeals to young musicians, who understand that music careers now often involve Web design, blogging and filmmaking. So does his reputation for forward thinking, as on last year’s Web-enhanced reissue of “My Life in the Bush of Ghosts,” his 1981 collage-funk collaboration with Brian Eno, and his more recent solo work. “He’s just kind of pursued what he finds interesting and hasn’t been specifically chasing after an audience, and I have a lot of respect for that,” said Win Butler of the Arcade Fire. That band has performed with Mr. Byrne on various occasions, and its cover of Talking Heads’ “This Must Be the Place (Naïve Melody)” is a blogosphere favorite. “I don’t think of him as a pop star, really. He’s like a scientist, or a professor.” Mr. Byrne appreciates being acknowledged by younger musicians, but he doesn’t seem nostalgic for the days when he was one himself. He likes the tributes best, he said, when they come from bands that “don’t sound anything like me, or Talking Heads.” Relations between Mr. Byrne and his former bandmates are famously strained, although they did manage to reunite for a few songs at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony in 2002. Mr. Byrne’s attitude seems best expressed in a short essay included in “Once in a Lifetime,” one of two extravagant Heads CD retrospectives released in the last few years. Addressing himself and his music in the third person (something he does in conversation too), he noted that he was “just not the same person” who created his early work, and that he “can’t go to that place anymore.” Progress and evolution are more important, he wrote, at any cost. Yet his latest musical project may capture the musical kinetics of Talking Heads better than anything Mr. Byrne has done since the band broke up in 1991. “Here Lies Love” was inspired by Imelda Marcos’s love of disco, so great that she installed a dance floor, complete with mirror ball, on the roof of the presidential palace in Manila. The work in progress was conceived for performance in a dance club, with an audience doing what one generally does in such places. (If the Carnegie Hall crowd needs to boogie at the Feb. 3 concert, perhaps the ushers will understand.) Mr. Byrne, who was born in Scotland and raised in Baltimore and has traveled widely, says he was attracted to Ms. Marcos’s story in part as a way to understand the inner workings of dictators, always a timely endeavor. “How do they justify — how does anyone justify — what might seem to be atrocious behavior?” he recalled wondering. In this case, he thought, maybe “dance music could be some sort of link: the way people sort of lose themselves at a rave or a club — maybe there’s something about it that connects to the feeling of somebody in power. Kind of a heady feeling, like you’re up in the clouds. And I thought maybe I could tell the story in that kind of setting. I thought that would be really neat.” Last February, at a rehearsal space amid the art galleries on West 26th Street, he prepared the “Here Lies Love” material for its world premiere, which took place in March at the Adelaide Bank Festival of Arts in Australia. Two singers flanked him on his right: Dana Diaz-Tutaan, who plays the Marcos role, and Ganda Suthivarakom, who plays Estrella Cumpas, the housekeeper-nanny who effectively raised Ms. Marcos. Dressed in a blue mechanic’s jumpsuit branded with the logo of Luaka Bop (his world music label), with his glasses perched low on his nose, Mr. Byrne played chucka-chucka chords on a blond Fender guitar. Above the musicians — the keyboardist Tim Regusis, the bassist Paul Frazier, the drummer Graham Hawthorne and the percussionist Mauro Refosco — the video designer Peter Norman projected remarkable clips from the Marcos era: Imelda dancing with Gerald R. Ford, dining with Donald Trump, kibitzing with Richard M. Nixon and George P. Shultz. Some scenes read as vaguely comic; others were genuinely disturbing, like a segment capturing hardscrabble street life in Manila. The songs conjured New York disco-rock of the ’70s and ’80s: a fusion that Talking Heads spearheaded, of course, and that is currently undergoing a revival. But the sound is not simply Heads redux. For one thing, much of the material is sung by the female vocalists, not Mr. Byrne. Furthermore, his (absent) collaborator on the project is the D.J. Norman Cook, a k a Fatboy Slim, who seemed to have added modern heft and a techno sheen to some of the beats. Another sign of Mr. Byrne’s constant forward motion is his voracious appetite for new music. He’s a regular visitor to the annual South by Southwest music festival Austin, Tex., where he will be a featured speaker in March. And any concertgoer in New York City is apt to spot him regularly, hanging out near the back of a room, generally without an entourage, his shock of near-white hair adding a few inches to his already impressive height. Last year he could be spotted sipping white wine in the lobby of Town Hall before a Cat Power performance, applauding the debut of Gnarls Barkley at Webster Hall and cheering the Brazilian funk artist Otto (who appears on a forthcoming Luaka Bop compilation) at Joe’s Pub. “He really keeps his finger on the pulse,” said Ms. Diaz-Tutaan, whom Mr. Byrne became interested in after hearing the CD her band, Apsci, recorded for the tiny progressive hip-hop label Quannum. “That’s really inspiring to me — that this guy who has been around for such a long time and has been one of my musical influences is keeping up with things on a more underground level. He’ll just ride his bike to a venue, go in, check out the band and ride home.” Mr. Byrne doesn’t seem to think there’s anything particularly remarkable about it. “Sure, I go out a lot,” he said. “I’m in New York, and I’m a music fan. But sometimes I go out to these shows and I go ‘Where are my peers?,’ you know? Where are the musicians from my generation, or the generation after mine? Don’t they go out to hear music? Do they just stay home? Are they doing drugs? What’s going on?” He laughed and shook his head. “Or maybe they’re just not interested anymore. They’re watching ‘Desperate Housewives.’ ” Correction: January 28, 2007: An article on Jan. 14 about David Byrne and his song cycle based on the life of Imelda Marcos, the former first lady of the Philippines, misidentified the ethnicity of a singer in the production. Ganda Suthivarakom is of Thai-Chinese descent; she is not Filipino. |

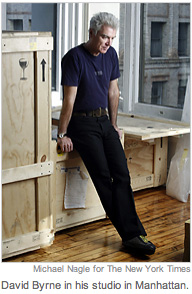

Mr. Byrne spoke recently over a late- afternoon coffee at his studio near Chinatown, sitting at a wooden farm table under a row of windows overlooking Broome Street. The walls of the loft space (a former sweatshop, he noted) are lined with book and CD shelves, or hung with curious objects, including a painting by the Rev. Howard Finster (who illustrated the cover of the Talking Heads album “Little Creatures”) and a pair of banners salvaged from a Mason hall.

Mr. Byrne spoke recently over a late- afternoon coffee at his studio near Chinatown, sitting at a wooden farm table under a row of windows overlooking Broome Street. The walls of the loft space (a former sweatshop, he noted) are lined with book and CD shelves, or hung with curious objects, including a painting by the Rev. Howard Finster (who illustrated the cover of the Talking Heads album “Little Creatures”) and a pair of banners salvaged from a Mason hall.