Bob the Builder

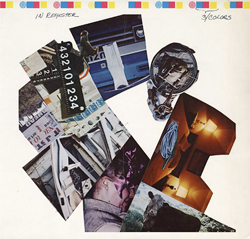

It was not unusual for a pop musician to approach a fine artist in those days; other contemporary artists had collaborated with pop bands in the late ’60s and early ’70s. I was pleasantly surprised, though, when Bob, who died this week, eschewed simply reproducing a work on the album jacket in favor of re-envisioning what the whole LP package could be. His package consisted of a conceptual collage piece in which the color separation layers — the cyan, magenta and yellow images that combined to make one full-color image — were, well, deconstructed. Only by rotating the LP and the separate plastic disc could one see — and then only intermittently — the three-color images included in the collage. It was a transparent explication of how the three-color process works, yet in this case, one could never see all the full-color images at the same time, as Bob had perversely scrambled the separations. Needless to say, the design posed some production problems for Warner Bros. Records, so it ended up a limited, but very large, 50,000-copy edition, released in addition to the regular, mass-produced version. Luckily, everyone shared in the crazy idea of making radical art that could also be popular. Nowadays there might be concerns about the return on investment, but at that time the label let these matters slide. I later became friends with Bob and his collaborators, and it was an incredible world to enter. I sensed immediately that Bob had never become cynical about his work. Even after he found success, he continued to see the world as a work of art that simply hadn’t been framed yet. Bob’s way of talking was a challenge to many — he spoke in constant puns and metaphors, like a stream-of-consciousness poet, and one had to suspend traditional forms of speech, understanding and discourse and go with the flow. It was liberating, if you could hang in there, and never mundane. Conversation was like one of his pieces: a crazy mishmash of images, multiple layers and references, and a spray of allusions that were simultaneously silly, profound and beautiful — he was the Neal Cassady of the art world. His life, and his relation to those around him, was just like his work; there was no separation and he never went out of character. The love of the world that was in the work was also in the man. Bob drank heavily. In the ’80s, I discovered him once at his studio on Lafayette Street, in mid-afternoon, with a glass of Jack in his hand. I, rock ’n’ roll guy, was amazed to see an established artist living one aspect of the rock ’n’ roll life much more intensely than I ever dared. I did wonder if some of the beautiful jumps and leaps in his conversation were partly alcohol-related, but his output remained transcendent, so I figured he was managing it. Being around Bob was often like being on some kind of ecstatic drug — he inspired those around him to not only think outside of the box, but to question the box’s very existence. He was driven to challenge himself. For his globe-spanning project, Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange, Bob collaborated with artisans and small factories in Chile, China, Cuba, Germany, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, the Soviet Union, Tibet and Venezuela over many years. In pre-“it is glorious to be rich” China, Bob worked with the oldest paper manufacturer in the world, while in India he worked with mud-manure straw clay. Suspicious of Bob’s motives, some countries forced him to wade through red tape, and his open attitude toward materials and creativity occasionally confounded his traditional artisan collaborators. The results, though, were sometimes wonderful, especially when he managed to break his own mold. Bob was extraordinarily generous. I don’t mean he gave away art — though he did that, too — but he was generous with his time and with his ideas and spirit. He started Change Inc., a foundation that awards grants to emerging artists who can’t pay their rent, utility or medical bills. No questions asked. He was, of course, famous for making art out of everyday junk he found on the street. One summer I went down to Captiva Island, Fla., where Bob had his main studio. I stayed across the road in one of the houses he had “saved,” and I spent a week or so writing a few songs. When I returned to New York, I left behind a pair of worn-out tennis shoes. A ghostly image of them showed up in a painting not long after. Bob’s generosity of vision was, it seemed to me, more profound than the financial kind. His openness and way of seeing was contagious and inspired others in their own work — not to imitate and make pseudo-Rauschenbergs, but to see the whole world as a work of art. As corny as that may sound, that’s what he sometimes did. David Byrne is a musician and visual artist. |

I approached Bob Rauschenberg in the mid-’80s to design a cover for the Talking Heads record “Speaking in Tongues.” I had recently seen some of his black-and-white photo collages at Leo Castelli’s gallery on West Broadway and thought they were amazing, and I wondered what he would do with an LP cover.

I approached Bob Rauschenberg in the mid-’80s to design a cover for the Talking Heads record “Speaking in Tongues.” I had recently seen some of his black-and-white photo collages at Leo Castelli’s gallery on West Broadway and thought they were amazing, and I wondered what he would do with an LP cover.