Concert Review: David Byrne, Toronto, October 29

By Mike Doherty, National Post — The Ampersand, 30 October 2008 [Link]

Many an adjective has been applied to David Byrne over his 30-plus-year career, but “nostalgic” isn’t one of them. The singer and guitarist has consistently refused to rejoin his former bandmates in Talking Heads for an album or tour since their early-‘90s break-up, and he’s been a mercurial solo artist, taking up and shedding musical styles as if he were changing clothes.

Still, one part of his oeuvre has always seemed particularly worth revisiting: the music he made with Brian Eno from 1978-81, which helped push pop music forward with its ambiguous textures and complex, African-influenced rhythms. This work includes three Eno-produced Talking Heads albums, Byrne’s score to the Twyla Tharp dance project The Catherine Wheel, and the collaborative masterpiece My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, an album whose widespread influence on hip-hop and dance music has far surpassed its commercial popularity.

The very existence of this year’s Byrne and Eno reunion album, Everything That Happens Will Happen Today, is cause for rejoicing, and the “Songs of David Byrne and Brian Eno” tour, which introduces the new album and delves into the earlier work, even more so. Even though Eno is loath to tour these days, Byrne and his 10-piece crew (four instrumentalists, three backing singers and three dancers) are more than capable of breathing new life into the duo’s studio concoctions.

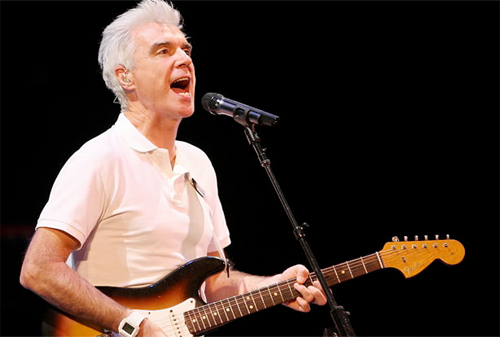

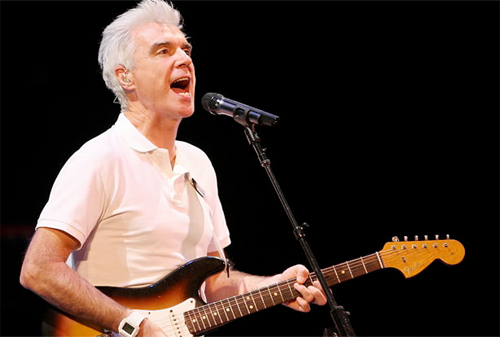

At Massey Hall, the 56-year-old Byrne looked decidedly less pasty and more relaxed than in his Talking Heads years; he sounded even better, his voice a more resonant and versatile instrument than ever.

The first number he sang, “Strange Overtones” from Everything that Happens, includes the lines, “This groove is out of fashion / These beats are twenty years old.” Indeed, we have heard chattering rhythms like this before (specifically on Eno and John Cale’s 1990 album Wrong Way Up). But if the new material is explicitly less forward-thinking than the Afro/Arabic/avant-exorcist grooves on Bush of Ghosts, Byrne’s assured performance underlined a compelling change of strategy: he and Eno now entice their listeners with warm washes of sound rather than confronting them outright with stabs of sonic weirdness.

Bush of Ghosts was represented in the setlist only by the roiling funk of “Help Me Somebody” -- it seemed a missed opportunity, perhaps predicated by the fact that Byrne doesn’t sing on the original (all the vocals are sampled, although surely he and his backing singers could have found a way to pull them off).

Musically, he offered few surprises, with faithful, albeit somewhat more organic and open-sounding, versions of his and Eno’s original songs. Byrne’s biggest innovation on this tour is a visual one: dancers Lily Baldwin, Natalie Kuhn, and Steven Reker expand on the vocabulary of movement that he has developed since Talking Heads’ video for “Once in a Lifetime,” exploring the interface between religious possession and technological control.

They often seemed to be performing tasks as if on an assembly line or in cubicles (one song found them swivelling and rolling around the stage on office chairs), or straining against patterns of movement suggested by the charged, circular grooves on songs such as “Cross-eyed and Painless” and “The Great Curve.” When they did break free -- engaging the backing singers in loose routines, bolting across the stage between Byrne and the microphone, or even, in Reker’s case, vaulting right over him -- the atmosphere was ecstatic, and the crowd was often brought to its feet.

In fact, so much was going on around the stage, with everyone dressed all in white, it was easy to lose Byrne in the shuffle. But during the last few songs -- a shimmying disco version of the formerly nervy “Air,” a triumphant run through “Burning Down the House” (a non-Eno track, but no one in the fist-pumping crowd seemed to care), and a closing run through the lullabye-esque title track to Everything that Happens -- everyone took a step back, leaving the focus squarely on Byrne, who played snarling lead guitar, busted out jerky dance moves, and sang in his newly rounded, confident tenor as everyone, dancers included, harmonized sweetly around him.

Byrne seemed happy and moved by the three enthusiastic standing ovations he received. If there’s one common thread running through all the phases of his career, it’s the belief that music should always be uplifting, even as it expresses doubt or warns of danger. His celebratory concert, happily, was no exception.